About this Series:

I think a lot about the songs I cover. And when I decide to record one, I do a ton of research on the song, its origins and author(s). I do this not only to better appreciate the nuances behind the lyrics, phrasing and arrangements, but to try to get in touch with the soul of the song, so I can really do it justice.

This series of blog posts aims to capture some of that research as a way to help others better appreciate the songs under discussion too. I’ll share some of the thinking behind my own arrangements and sonic treatments of the song, along with what I learned about the relative “rightness” of those approaches during the recording and performing process.

My hope is that whether you’re a songwriter/performer, a music writer, or just a fan who is interested in how songs get written and recorded, you’ll find something to make you revisit or begin exploring the tune and/or artist under discussion.

As always, if you have further thoughts or info on the song or my approach to it, feel free to share them in the comments section below. I’d love to hear from you!

——————

How to write a song about such crazy times? As I write this, the U.S. is suffering through a second wave (if that’s what it really is, or just a continuation of the first one) of the COVID-19 pandemic, which could possibly lead to yet further drastic quarantines and social isolation. We continue to struggle with our longtime national divide over race and the wanton, unnecessary use of force by police officers against black and brown people. And to compound matters, we’re dealing (unsuccessfully, by all measures except the perversely out-of-step ones of the stock market) with the worst unemployment, economic slowdown, and housing crisis since the Great Depression.

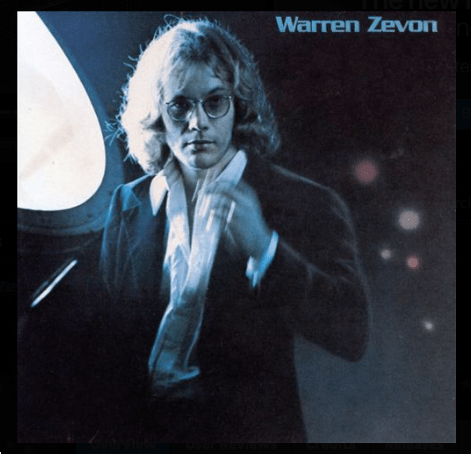

As I was thinking about how anyone could possibly encapsule and respond to such a dismaying coincidence of social and natural traumas, it dawned on me that there’s already an existing song that does exactly that: Warren Zevon’s “Mohammed’s Radio.”

Zevon’s lyrics for this tune deal directly with the angst and despair brought on by feeling pent-up, wantonly preyed upon by law enforcement, and desperate to survive in a depressed economy — in a way that is both dryly ironic about yet deeply sympathetic to the human impulses and longings involved. In short, it’s a perfect song for our time — despite having been penned by Zevon in the early 70s, almost half a century ago (!).

The first verse sets a painfully recognizable scene, for those of us tired of being quarantined and constantly (sometimes contradictorily) being told what (or what not) to do by public officials and politicians:

Everybody’s restless

And they got no place to go

Someone’s always trying to tell them

Something they already know

So their anger and resentment flow

Sound familiar? Even more startlingly, the second verse addresses the problem of police violence, dryly and pithily condemning the compensatory psychology behind law enforcement’s frequent flare-ups:

You know the sheriff’s got his problems too

And he will surely take them out on you

On the other side of the scale from the sheriff’s personal problems, Zevon gestures at the wider landscape of societal inequality and its accompanying feelings of hopelessness in the third verse:

Everybody’s desperate

Trying to make ends meet

Work all day and still can’t pay

The price of gasoline and meat

Alas, their lives are incomplete

That last line gets me every time: “Alas,” Zevon archly intones, “their lives are incomplete.” Though you could read that statement as detached and harshly judgemental —as critics who blithely throw around labels like “misanthropic” in their assessements of Zevon’s work tend to do — I see it rather as a kind of knowing and sympathetic gesture. The equation of their inability to afford “gasoline and meat” with their lives being “incomplete” rings true with our own, current confrontation with the depradations of consumer capitalism run amuck, which has resulted in a stark economic divide that deprives the working classes of even the most basic commodities. Their lives are “incomplete” not because they overvalue such things — gas and meat are not trivial baubles or do-dads — but because they have literally been deprived of these necessities. In the context of its surrounding, factual lament, Zevon’s “Alas” has a richer, overdetermined ring to it.

In counterpart to the relentlessly negative feelings “everybody” is subject to in the song’s verses, Zevon offers the “sweet and soulful” solace of music — which even the “village idiot” can comprehend, and which makes his face come “all aglow” — along with (crucially) the hope that somehow, someday, the “righteous… might just come.” The latter is a longing that the general, flanked by his “aide de camp” (who else but Zevon could so seamlessly integrate that phrase into a pop song?) seems to share. In an unexpected twist, Zevon reveals that even that military leader stays “watchful for Mohammed’s lamp.”

Those final details are why I contend that “Radio” is ultimately a hopeful rather than a depressing or parodic song. Contra his reputation for being misanthropic and vile-spewing (see the AllMusic review of the self-titled album “Radio” appears on), this song highlights Zevon’s eye for telling details that convey both a cynical realism and a sense of wonder at humanity’s resilience. In short, Zevon has a knack for conveying life’s elusive, multivalent ironies. Rather than emphasizing humanity’s misguided hopelessness, “Mohammed’s Radio” highlights the human capacity for hope against all odds. Zevon’s attitude toward the characters in this song isn’t aloof or dismissive; it’s wryly philosophical.

Sadly, “Radio’s” brilliance was overshadowed on that first (real) album of Zevon’s by several other amazing tunes, including “Poor Poor Pitiful Me,” “Desperadoes Under the Eves” and “Carmelita.” (The AllMusic.com review of the album mentions every other song but this one.) I found it to be well worth studying, particularly in light of its resonance with our current world situation.

Jackson Browne’s Approach to Recording “Radio”

In his review of Warren Zevon (the album), Mark Deming characterizes Zevon’s music as being so “full of blood, bile, and mean-spirited irony” that even “the glossy surfaces of Jackson Browne’s production” couldn’t “disguise the bitter heart of the songs” on it. This assessment seems wrong-headed in a number of ways, particularly in its suggestion of a mis-match between Browne’s approach and Zevon’s raw material.

The fact of the matter is, as Crystal Zevon details in her biography of Warren, I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead, the album was actually a kind of family affair, with Browne eliciting contributions from his and Warren’s incredibly talented L.A. musician friends, including members of the Beach Boys and the Eagles (Don Henley and Glenn Frey) as well as Bonnie Raitt, Stevie Nicks, Lindsey Buckingham, Phil Everly (of the Everly Brothers, who Zevon had toured with), David Lindley, Rolling Stones saxophonist Bobby Keyes, and many others. As Crystal Zevon concludes, “It seemed there was no one who wasn’t flattered and delighted to take part in the recording of Warren’s debut album” (p. 107).

I think Browne & team’s treatments are spot-on in their approach, in that they highlight Zevon’s musical gifts without undermining the inimitable mix of wit, sting and sweetness of his lyrics. As Deming admits, “for all their darkness, Zevon’s songs also possessed a steely intelligence, a winning wit, and an unusually sophisticated melodic sense, and he certainly made the most of the high-priced help who backed him on the album.” What resulted from those recording sessions and players “remains a black-hearted pop delight,” he adds.

Browne & team’s approach is clearly FM radio friendly and pop-oriented; in that regard, it’s very much in the vein of other 1970s L.A. artists like Fleetwood Mac, the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, Bonnie Raitt and Browne himself. Though Zevon’s recordings usually feature his piano, for this tune Browne opted to make the guitars and bass more prominent than the keys, though the piano fills become more noticeable during the turnarounds and especially toward the song’s end. For the most part, though, it’s Waddy Wachtel’s (or Ned Doheny’s? Lindsey Buckingham’s? Browne’s? — the credits aren’t clear) delicate triad-based electric guitar fills that take center stage. Marty Davis adds some nifty slides and grace notes on bass as well.

Most interestingly, Browne inserts saxophones (courtesy of Bobby Keys) and soulful female vocals by Rosemary Butler beginning with the first chorus. The sax parts lend the song a slightly dark, “late night” vibe a la Steely Dan (think “Deacon Blues” or “Black Cow” from Aja). The saxes and backing vocals continue to the song’s big finish, which features a tag of the song’s title phrase over a slow retard. Overall, the production is quite tasteful and mainstream — it’s not at all experimental or boundary-crossing. Browne clearly didn’t want to distract from the song’s lovely melody and subtle lyrics.

About My Approach

Here’s my version of this incredible tune.

My recording sticks to the same basic framework as Browne’s, though it’s much less polished and professional (I don’t have the chops of his session players, obviously, and I recorded it in my basement rather than a high-end L.A. studio). I don’t play piano or saxophone, but I did my best to emulate the delicate guitar fills, and I added some rudimentary slide touches on my lap steel (interestingly, David Lindley doesn’t appear on Zevon’s recording, though he was there for the sessions).

My daughter Eleanor provides the lovely backing vocals from the third chorus on; I especially love the vocal echoes she provides for the phrases “up all night” and “just be right” in the last verse, so I doubled those, panning them to both sides. The kid’s got some serious talent, no? She puts my wavering vocals to shame.

Some Things I Learned

First off, I learned how hard it is to even approximate Zevon’s cool, cynical delivery. See for example, his phrasing on the word “Alas” versus Linda Rondstadt’s version and mine on the same. It’s inimitable, and absolutely crucial to how his songs come across.

Zevon’s recording includes some subtlely tricky percussive treatments and rhythmic changes on the bridge, to emphasize key phrases in the lyrics. I found it hard to emulate those, so I wound up just going heavy on my crash cymbals instead. I’m not sure that works though; this is a ballad, not a rocker, obviously.

I also simplified the tune’s intro riff, smoothing out Zevon’s quick da-da-DAH! rhythm. Mine is more like a “da, da…dah,” with equal emphasis and rhythmic spacing between all three notes, versus Zevon’s quick, shortened “da‘s” followed by an emphatic “DAH.” My approach just felt like a quieter, less fanfare-ish way to enter the song, and it also worked well for the repetition on the turnaround after the second chorus.

Though my mix of the song is super rudimentary and the overall production pretty rough and homemade sounding, I hope it manages to capture something of the spirit of this great, unique tune. After spending three weeks recording it, I’m more convinced than ever that its potent blend of desperation, angry resignation, and flickering hope provides the perfect accompaniment to our current national situation.